Through legal action, the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) aims to prevent censorship of student press within high schools and colleges.

Souderton is one of the districts that protect student press; however, many students aren’t as lucky.

The standard of student press rights in the U.S. has varied over past decades, with landmark Supreme Court cases varying the level of control school administrations have over their students’ rights to the First Amendment.

Beginning in 1969, students of Harding Junior High School in Des Moines, Illinois wore black armbands to protest the Vietnam War.

After the students were suspended by the school district, the students filed a lawsuit against the district for violating their freedom of speech.

The case, known as Tinker v. Des Moines, was eventually brought to the U.S. Supreme Court where the court ruled in favor of the students.

The court stated that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The landmark ruling of Tinker v. Des Moines set the general precedent that schools cannot lawfully suppress student’s First Amendment rights just because they are at school.

This precedent was challenged by the 1988 case of Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier.

For their school’s newspaper, The Spectrum, student journalists wrote and planned to publish articles about teen pregnancy and students of divorced parents. When the paper went to be published, their principal interfered and removed the articles without the students’ consent.

Claiming that their principal’s actions violated their First Amendment rights, the students sued their school.

Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the judges ruled that the principal’s actions did not in fact violate their freedom of speech and that administrators had the right to censor student press if they believed the content was inappropriate or misrepresented the school.

However, the vague ruling of Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier left room for school administrators throughout the country to manipulate their power to censor content, potentially leaving their students without a responsible forum to express their perspectives and issues that are important to them. This setback for students’ constitutional rights still impacts young journalists today.

According to the SPLC, in 2022, the school board of Northwest Public Schools in Nebraska discontinued their high school’s student-run newspaper, the Viking Saga, after students published two articles regarding Pride Month that administration deemed “inappropriate,” one about the history of Pride Month and the other an opinion piece denouncing Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill.

In an article by The Independent, the Vice President of Northwest Public Schools’ school board recounted that administration began to consider shutting down their students’ newspaper when the district lost the ability to control students from publishing “inappropriate content.”

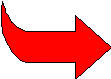

Along with being censored for attempting to educate their communities on relevant social issues, student journalists have also been censored for voicing concern for their school’s policies that they’d like to see reformed.

For example, according to another report published by the SPLC, in New York in 2020, when a student attempted to publish an opinion article on how the quality of learning at her school has varied and decreased due to virtual classes, her school’s principal “held the story for over a month, requiring that another article be included in the paper that was supportive of the school’s distance learning program.”

Therefore, while attempting to refine and protect their school’s image, the administration consequently prevented their students from not only voicing their unique perspectives in a reasonable manner, but also inadvertently removed the autonomy students could have over decisions regarding their education by not respecting their input.

Through the New Voices legislation, student journalists like those at the Viking Saga or this New York school would be protected under the law to justly exercise their intrinsic First Amendment rights.

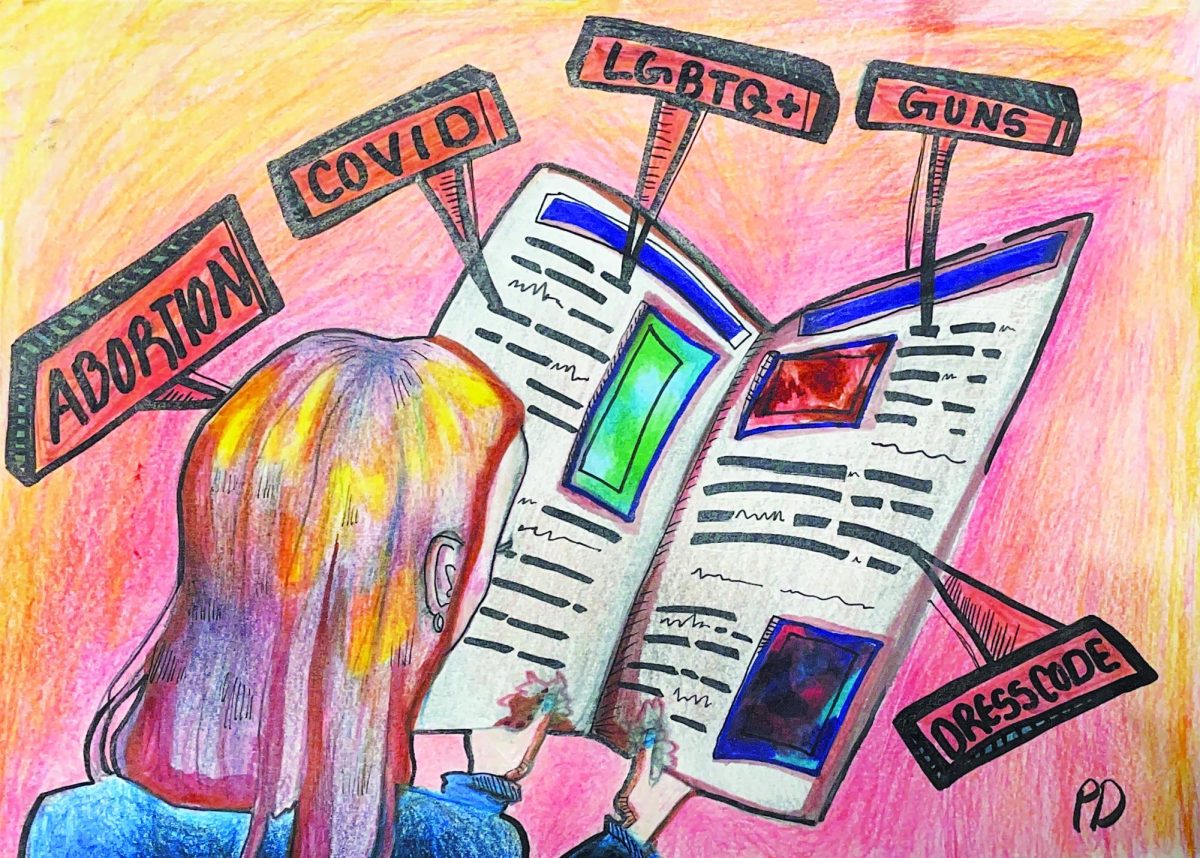

At the end of the day, high school student press is a microcosm of the “real world.” Just as with publications like The New York Times or The Philadelphia Inquirer, student newspapers serve their district by covering topics relevant to their community and provide an opportunity for students to share their perspectives via a credible source.

Just as with professional publications, students should reserve the right to openly share their perspectives about their school’s policies and practices without fear of censorship, just as professional publications hold politicians accountable.

New Voices legislation has passed in 17 states, with the bill being introduced in seven other states this year, including Pennsylvania. According to the SPLC, while Pa. administrative code prevents student press from being censored just because administration claims it’s critical of their school, this fails to effectively uphold Pennsylvania student journalists’ rights to free speech.

The SPLC writes on their website that Pennsylvania’s code also “continues to allow for prior review of student media and fails to protect student media advisers from retaliation when they support their student journalists’ press freedom.”

This sense of covert intimidation many student journalists may feel from administrators to censor or restrict their reporting would be destabilized by New Voices legislation and help to empower student journalists throughout Pennsylvania.

While New Voices legislation doesn’t allow students to publish just anything, such as material that violates federal or state law, New Voices will provide overarching protections to student journalists.

WWSI: New Voices protects student press rights

To protect student journalists’ right to free speech, the Student Press Law Center created the New Voices legislation. Currently, 17 states have passed this legislation, ensuring students are protected under the law to publish without fear of censorship from their administration.

Arrowhead Editorial Board

•

December 18, 2023

New Voices legislation allows students to exercise there first amendment right legally, expanding the coverage of student journalism, and the student voice as a whole.

0

Tags:

More to Discover